Why Twitter can't agree on a simple math equation

I came across this tweet this morning, followed by the replies of approximately 9.7 thousand people arguing over what the correct answer actually is.

how smart are my oomfs pic.twitter.com/YVxtzhNx4c

— dev ᴺᴹ ᴬᴳ (@iambuterastann) November 13, 2020

The complete and total conviction in the replies is notable. I’ve seen the same thing on Facebook and I often get caught up with the verocity that people argue with each other. The trick is usually the same, but in this specific case users come mostly to two answers: \(1\) and \(9\). Which is right? The answer is that they both are! Read on for why.

What they’re seeing

As mentioned, there are roughly two categories of answers: \(1\) and \(9\). There’s also some weird ones, like \(0\) being another common one, but these are primarily arithmetic mistakes. First, let’s focus on how someone would arrive at \(9\).

Remember PEMDAS? You may have also learned it as BEDMAS. This is a rule taught that helps you remember the order of operations for algebraic notation. We follow this order: Parentheses, exponents, multiplication / division, and then addition / subtraction. You do each of these steps from left to right. Note that multiplication / division as well as addition / subtraction happen at the same time, rather than multiplication followed by division for example (ironically that leads to a valid answer for invalid reasons and further fuels argument).

If you strictly follow PEMDAS you get this result:

\[6 \div 2(1 + 2) \\ 6 \div 2(3) \\ 6 \div 2 \times 3 \\ 9\]Did you see what happened in that second step? Let’s re-look:

\[6 \div 2(3) \\ 6 \div 2 \times 3\]Keep that in mind as we look at what the second category of users, those who concluded the answer is \(1\), are doing:

\[6 \div 2(1 + 2)\\ 6 \div 2(3)\\ 6 \div 6\\ 1\]Did you see the difference? Users who conclude \(1\) multiplied \(2\) and \(3\) together before evaluating the multiplication and division left-to-right. You might think “that’s not following PEMDAS!” and you would be right. So why are they doing this?

The notation \(2(3)\) can be called an implicit multiplication by juxtaposition. It’s implicit because there is no actual multiplication symbol, and it’s understood to be multiplication with the brackets because it’s juxtaposed (“close to”) with them.

In some notations it is a common convention to treat these implied multiplications as higher priority than other multiplications. For example you might see authors write things like \(\frac{x}{2(3x + y)}\) as \(x \div 2(3x + y)\), which is different than \(x \div 2 \times (3x + y)\).

Math is a shared notion

So who is correct? A math expression must have only one real answer right? The point of math is it is supposed to be true and inarguable, right?

That’s all fair, but “math” is different than “math notation”. Mathematics models real relationships in our physical world, but the things we write down are just an agreed upon language for communicating it.

For example, if there is a four legged creature with a cute nose right in front of me:

and I tell you that I see a dog, you know what I mean. But if I only spoke Spanish and I called it un perro, you may not know what I meant. That doesn’t change the inarguable fact that there is a furry four legged creature in front of me, but you might only understand what I’m trying to communicate if we’re speaking the same notation.

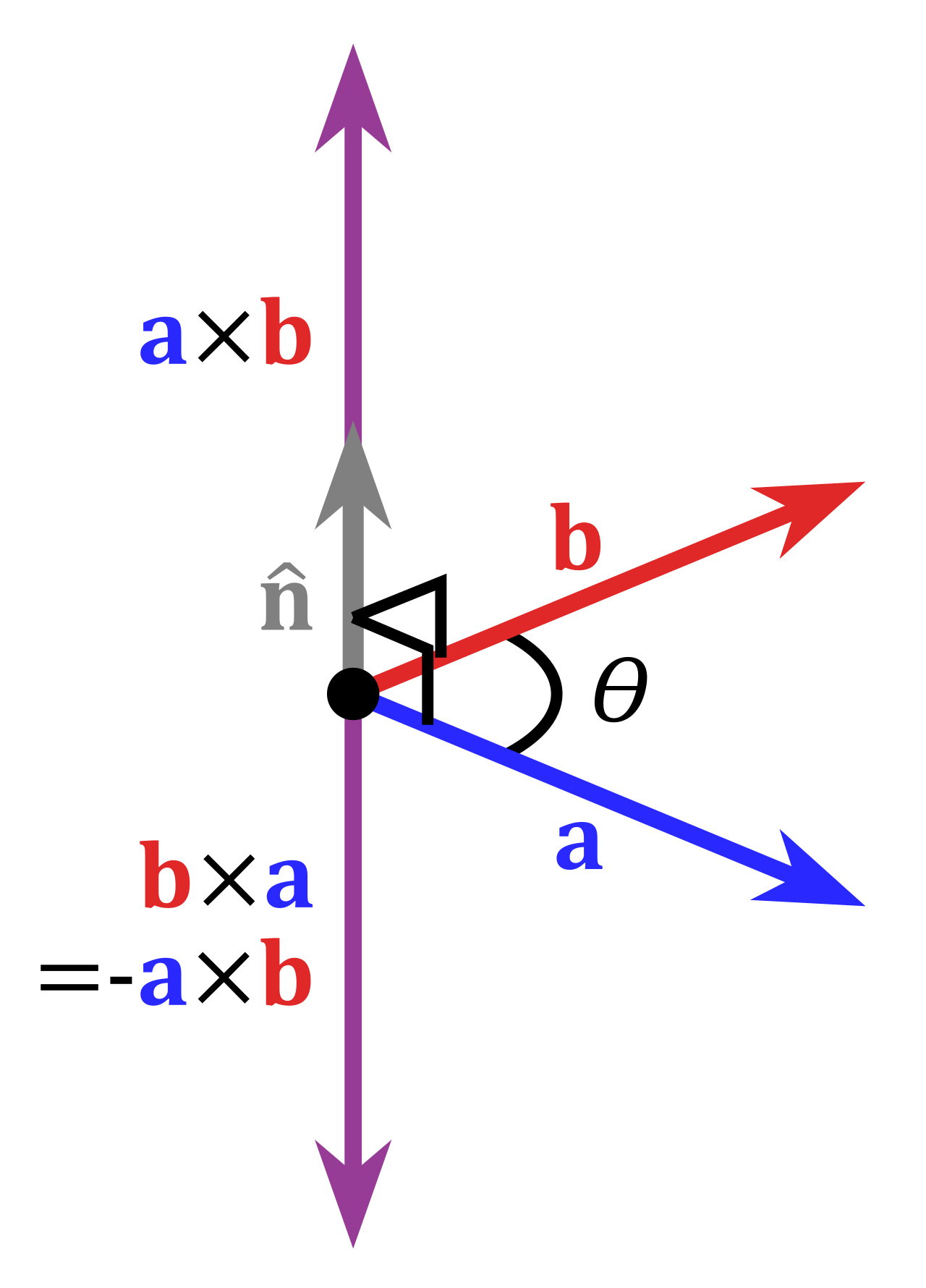

There’s lots of examples of this in math. Take something as simple as \(\times\). It should always mean multiplication right? Well, in vector algebra, everyone agreed that \(\times\) actually means something called the cross product of two vectors, denoted by the formula \(a \times b = \left\| a \right\| \left\| b \right\| \sin(\theta) n\) or to demonstrate visually:

There is some overlapping intuition, but this obviously looks and feels nothing like arithmetic multiplication, which is a series of repeated additions. However that’s what we decided to use \(\times\) for when talking about vectors. There are many examples of overlapping notation in math. As long as we agree and can communicate mathematical ideas, the notation isn’t really important.

So what users really disagree about is how to read this equation. Does the author who wrote this equation mean \(6 \div 2 \times (1 + 2)\) or do they mean \(6 \div (2 \times (1 + 2))\)? If this was in a textbook, or part of a larger series of equations, it would be clear from the context. With only this single equation to go on, it’s actually unclear what the author intended. Both interpretations are valid.

Conclusion

Of course the vagueness is deliberate in this case. It gets everyone on social media riled up as they think obviously their understanding is correct and obviously the other person is wrong. Didn’t they take 5th grade math?! But really – both groups are making reasonable interpretations and the equation itself is poorly written. If you were to give someone an equation with no other context at all, you should always use appropriate brackets to make it clear what you are communicating.

For more fun, you can see that even calculators themselves will differ on how to interpret this question. Some calculators process input left-to-right, some follow PEMDAS, and others will follow PEMDAS while giving implicit multiplication by juxtaposition a higher priority.

Different calculators give different answers - it depends on the choices made by the people making them. In the last pic it automatically added parentheses when giving the answer, it’s just down to convention chosen: pic.twitter.com/DB9J9j2zTx

— Dave (@DavePunFun) November 13, 2020

The real solution is to make this a more official rule that standard education teaches. Right now this is something that students in later education mostly learn by convention – which leads to a lot of confusion when people clearly interpret it differently but have a hard time explaining why. Textbooks can also be awful as they might explain PEMDAS and then give the implicit multiplication priority with no explicit mention of how that works.

Anyway, I see something similar on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter every few months and I thought it was worth writing up a beginner-friendly explanation that I can reference later. Hopefully it was helpful to you too!